New Year's Day 1915 was welcomed by SM U 24 (Kptlt. Rudolf Schneider) with a very special kind of fireworks, when it sank the old battleship HMS Formidable (15,000 tons) in the Western Channel.

In February 1915 then, Admiral von Pohl's plans were realized: The seas around the British isles were declared a war zone by the German government and any ship found there on or after 18th February faced sinking without warning: unrestricted U-boat warfare began for the first time in history. A neutral flag was considered to be no guarantee for safety, it was regarded as a common war deception: The British Cunard liner RMS Lusitania e.g. flew the Stars and Stripes in the Irish Sea on 31st January because U-boats (SM U 21) were reported to be in the vicinity. U-boat skippers were ordered to be absolutely sure a ship was neutral before sparing it.

The famous first "all-big-gun" battleship HMS Dreadnought, which never fired a shot in anger, was able to deliver a deadly and devastating blow to Germany's submarines on 18th March 1915, when it rammed and sank the newly commissioned SM U 29, which was commanded by the famous ace Kptlt. Otto Weddigen. Before sinking, the U-boat showed its sharp bow with the number "29" clearly visible for a last farewell. The death of Germany's most famous submariner and his crew was a boost of morale for the British and the cause of great sorrow on the German side.

|

The war against the merchants was thriving and by the end of April the U-boats had been able to sink 39 vessels at an own loss of three U-boats. Probably the most spectacular incident of the First World War happened on 7th May 1915, when SM U 20 (Kptlt. Walther Schwieger) fired one torpedo aimed at RMS Lusitania (30,000 tons) south of Ireland. After the explosion of the torpedo, the proud liner was shattered by a devastating second explosion (which was caused by coal dust) and sank within 18 mins with the loss of nearly 1,200 lives, among them 128 Americans. 15 mins after he had fired his torpedo, Kptlt. Schwieger, baffled by the terrible effect of his attack, noted in his war diary: |

Kptlt. Walther Schwieger (1885 - 1917) |

"It looks as if the ship will stay afloat only for a very short time. [I gave order to] dive to 25 metres and leave the area seawards. I couldn't have fired another torpedo into this mass of humans desperately trying to save themselves".

Although the German U-boat had every right to torpedo the ship - she was registered as a vessel of the British Fleet Reserve, she travelled in a declared war zone and in her cargo holds she was carrying rifles and explosives and thus was a rightful target - the sinking caused sharp American protest, resulting in a German order to leave passenger liners unharmed.

Despite of that U-boat activity increased and in August 1915 the sinkings by German U-boats (185,800 tons) bypassed the monthly building rates in British shipyards. On 19th August 1915, the debate about the U-boats heated up again, when SM U 24 (Kptlt. Rudolf Schneider) sank RMS Arabic (15,800 tons) with one torpedo, mistaking it for a troop transport. The liner sank in 10 mins with 44 casualties, among them 3 Americans. Again sharp American protests followed.

The German Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg feared the intervention of the Americans, if unrestricted U-boat warfare continued. Although the Chief of the German Naval Staff, Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff, promised the collapse of the British within six months, if he had free hand at sea, before US intervention would take effect - a fairly accurate assessment of the situation - Bethmann-Hollweg achieved a prohibition of attacking passenger ships except under prize rules by the end of August. But U-boat warfare according to prize rules was too risky in British waters. This and the possibility of confusing passenger ships with other ships led to the refraining of U-boat skippers from attacks. On 20th September 1915, the U-boats were withdrawn from British waters, the focus of the U-boat campaign shifted to the Mediterranean with plenty of targets and virtually no Americans present.

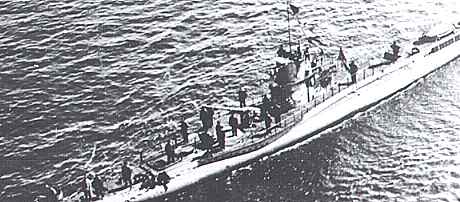

SM UB 64

At the end of 1915, about 855,000 tons of shipping had been lost, with 20 U-boats sunk. 94 ships were lost to mines laid by German mine laying "UC"-class U-boats operating under the command of the Flandern Flotilla (Commodore Andreas Michelsen) from the Belgian ports Brügge and Zeebrügge. Also stationed there were the "UB"-class coastal submarines. One of them, SM UB 13 under the command of Oblt.z.S. Athur Metz, sank on 15th March 1916 the Dutch steamer SS Tubantia which was supposed to have had German gold treasures on board. This affair was accompanied by fairly mysterious involvements of intelligence agencies and until today the mystery of the Tubantia, her cargo and the reason of her sinking, has not been properly solved. On 24th March 1916, another of Michelsen's boats, SM UB 29 (Oblt.z.S. Herbert Pustkuchen) inflicted another unwelcome diplomatic melée, when it torpedoed the French cross-Channel ferry Sussex (1,350 tons), mistaking it for a minelayer, with eighty casualties, among them 25 Americans. The damaged ferry was then towed to Boulogne. Following were sharp American protests, resulting in a total cancellation of the U-boat campaign around the British isles on 24th April 1916.

View of the control room of a German WW I U-boat.

Birth of the Q-ship

In 1915, Britain was in desperate need for a countermeasure against the U-boat. Sound detection gear and depth charges were still in their infancy, and the only means to sink a submarine was either by gunfire or by ramming. The problem was to lure the U-boat to stay on the surface rather than seeking safety in the deep of the sea. The solution to this problem was the creation of one of the closest guarded secrets of the war: the Q-Ship. This "U-Boot-Falle" (U-boat trap) was an old looking tramp steamer with hidden guns and torpedoes. Because of its load of wooden caskets, wood or cork, it very nearly was unsinkable. The idea was to lure the U-boat to attack the Q-Ship with its deck gun at close range as torpedoes would not sink the vessel. In a split of a second then the masquerade would be put to an end, the White Ensign would be hoisted and the U-boat would be in a deadly cross fire.

Barralong incident

The new weapon proved to be successful for the first time on 24th July 1915, when SM U 36 became the first U-boat to be sunk by a Q-Ship (HMS Prince Charles commanded by Lieutenant Mark Wardlaw RN). A particularly nasty incident took place on 19th August 1915: SM U 27 (Kptlt. Bernd Wegener) was sunk by the Q-Ship HMS Baralong (Lieutenant Godfrey Herbert RN). Herbert, enraged about Germans in general and U-boat warfare in particular, ordered that all German survivors, among them the commander of SM U 27, should be executed on the spot. Although the British Admiralty tried to keep this event as a secret, news spread out to Germany and the infamous "Baralong" incident - a war crime which was never prosecuted - had its share in promoting cruelty at sea. Once the Germans learned about the Q-Ships, U-boat skippers tended to be more careful and quite frequently the U-boat escaped or even sank its attacker.

One particularly dramatic engagement happened on 8th August 1917 120 miles west of Ouessant. SM UC 71 (Oblt.z.S. Reinhold Saltzwedel) was en clenched in a fight with the Q-Ship HMS Dunraven (Captain Gordon Campbell RN VC *). After an eight hour relentless fight with the repeated mutual exchange of gunfire and torpedoes, the unharmed SM UC 71 left the Q-Ship ablaze and in a sinking condition. This duel can be considered as a remarkable example of bravery on the British side (two members of the crew were awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest British decoration for valour) and coolness and skill of the German commander. Captain Campbell later wrote:

"It had been a fair and honest fight, and I lost it. Referring to my crew, words cannot express what I am feeling. No one let me down. No one could have done better."

But despite of these spectacular actions and romanization, Q-Ships did not prove to be that successful: In 150 engagements they were able to kill 14 U-boats (about 10% of all U-boats lost) and damaged 60 at an own loss of 27 out of 200. The only truly working counter measure against merchant raiders and U-boats - the convoy system - was well known to the Royal Navy since the times of the Spanish Armada, but they were reluctant to introduce it again - which should demand a terrible toll.

* Captain Campbell was awarded the Victoria Cross in February 1917 for the sinking of SM U-83.

See chapter 4. Deadly Mediterranean.